Insights from social psychology

In brief

How are women and men’s expected pension benefits related to their expectations about their life circumstances after retirement and the relation with their labour market decisions? How can the framing of communication about the impact of labour market decisions on future pension outcomes affect a person’s evaluations of these decisions? These are the questions that the psychological part of MIGAPE aims to answer.

To read

See the last section in our publication on main findings

Pension-Related comparative Optimism and Labour Market Participation

How is the expected pension benefit of men and women related to their expectations about their life circumstances after retirement and how do these expectations affect their labour market decisions? Among the psychological factors that may affect women’s employment situations are their future expectations, in particular those concerning their financial situation, health, and their relationship status.

How is the expected pension benefit of men and women related to their expectations about their life circumstances after retirement and how do these expectations affect their labour market decisions? Among the psychological factors that may affect women’s employment situations are their future expectations, in particular those concerning their financial situation, health, and their relationship status.

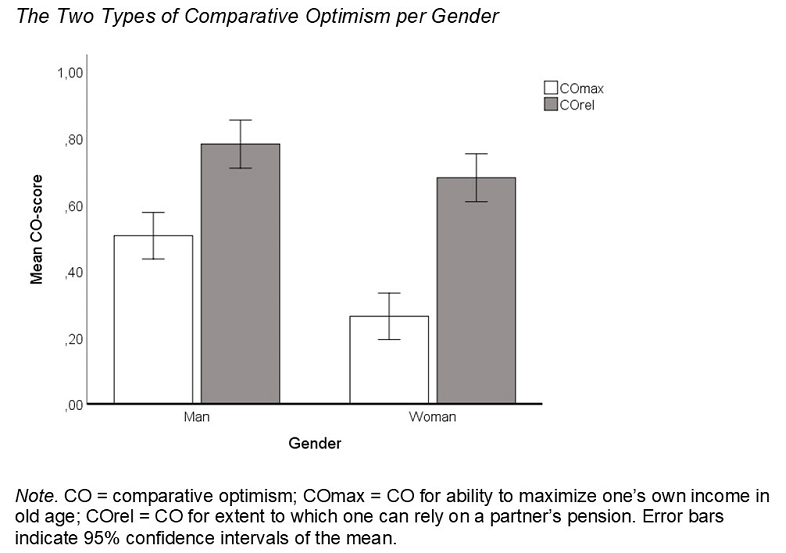

Our main interest is in comparative optimism – the belief that one’s future will be better than the future of other similar people. Information provided by governments on how career steps affect future pension benefits typically describes implications for people in general. But even when people agree that the financial future of individuals with certain career choices may look gloomy, they may not act on that insight because they believe that they themselves will escape that destiny. We collected survey data among men and women between ages 25 and 60 in Belgium. We asked respondents to judge the likelihood of 16 life events. Half of these were relevant for the ability to maximise one’s income in old age. The other questions were relevant for the capacity to rely on the partner for financial security after retirement. We found strong evidence of comparative optimism among men and women at active ages in most (but not all) events.

Participants felt that they were more likely than the average individual of their age, gender, and educational level to experience most of the life circumstances that would benefit their financial situation after retirement, and less likely than average to experience events that would threaten that financial situation. Men showed even stronger comparative optimism than women. This finding counters the hypothesis that some of the differences between men and women in labour market behaviour could be explained by the supposed greater comparative optimism of women about their financial situation in old age. However, women reported less active information seeking and scored poorer on a pension knowledge quiz compared to men. The gender difference in pension knowledge could not be explained by a standard measure of financial literacy as these two measures were only weakly correlated.

The Effect of Message Framing on Pension-relevant Career Preferences and Expectations.

The second issue we address is how the framing of communication about the impact of labour market decisions on future pension outcomes affects a person’s evaluations of these decisions. Message framing involves the extent to which the message focuses on what individuals will gain by doing X (gain frame) or in terms of what they may lose by not doing X, or doing Y (loss frame). It is known to be an important determinant of the persuasiveness of messages.

The second issue we address is how the framing of communication about the impact of labour market decisions on future pension outcomes affects a person’s evaluations of these decisions. Message framing involves the extent to which the message focuses on what individuals will gain by doing X (gain frame) or in terms of what they may lose by not doing X, or doing Y (loss frame). It is known to be an important determinant of the persuasiveness of messages.

We therefore had participants in an experiment respond to dilemmas described in vignettes about work decisions: taking or not taking a job; working full-time or part-time. In each dilemma, one option was secure from the point of view of maximising one’s future pension, and another option was insecure. We examined how and to what extent emphasizing the consequences for one’s pension of either the secure option (gain frame) or the insecure option (loss frame) would make people favour the secure option.

Where we did find framing effects, they involved greater gravitation towards the secure option after having read about the dilemma in a loss frame than after having read about it in a gain frame. Hence, if a message’s goal is to nudge or empower women towards accruing adequate pension rights, then there is reason to recommend the use of a loss frame in messages about the pension implications of, say, taking up full-time versus part-time work. Interestingly, the framing study also revealed that women were more willing than men to take their family’s interest into account when expressing their personal preference. Moreover, men felt that decisions that were optimal for men in general were not necessarily optimal for them, whereas women did not show such an other-self difference.

For more information

- See the last section in our publication on main findings